Under Georgia’s new school voucher program’s guidelines, families receive $6,500 per year for each child to pay for the switch to a private school or homeschool or other educational supports. Justin Taylor/The Current GA/CatchLight Local

This story was done in collaboration with The Current GA and is part of an ongoing series examining Georgia’s school voucher program.

Georgia’s new program to subsidize private education has helped more than 8,000 children move from public schools with low test score averages to educational organizations predominantly affiliated with Christian churches, data from the Georgia Education Savings Authority shows.

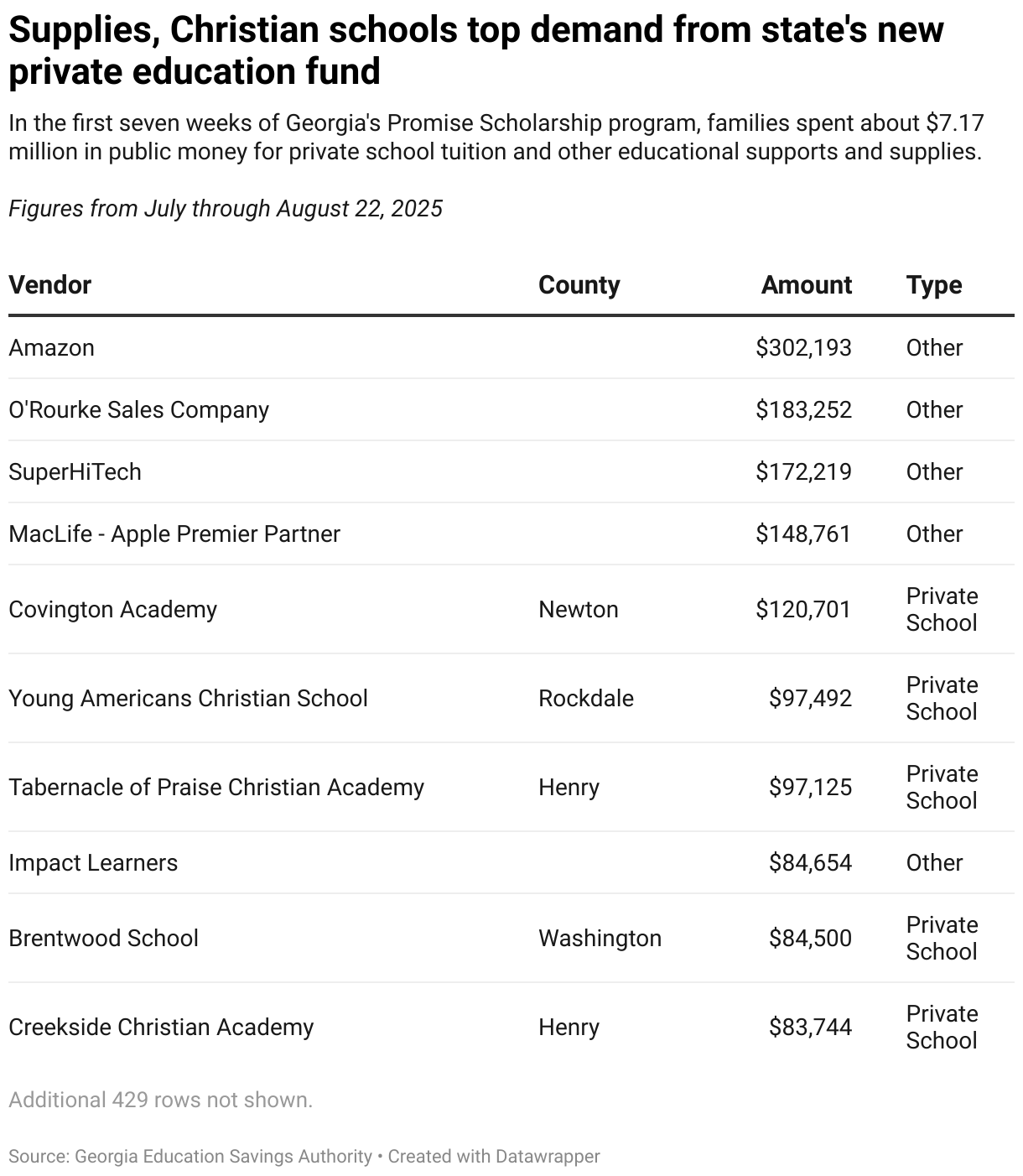

About $5.4 million of the $7.1 million distributed by the state authority at the start of the fall school semester went to 286 private schools serving 85 counties and nine cities, according to a data investigation by The Current GA and Georgia Recorder.

The remaining cash — $1.7 million — went to 153 companies, including giant retailer Amazon, that sell school supplies such as computers, tablets and books, records show.

As many as 8,600 private students make up the first cohort receiving the Georgia Promise Scholarship, the program approved in spring 2024 by the Republican-led state legislature and Gov. Brian Kemp. Eligible children must live in areas served by the lowest-performing 25% of the state’s public schools.

Under the program’s guidelines, families receive $6,500 per year for each child to pay for the switch to a private school or homeschool or other educational supports. Parents receive the money through an online state portal, where they then allocate the dollars to an approved private school or to a company to purchase educational materials or services.

The new state agency overseeing the voucher program spent more than a year finalizing rules, setting up an application portal and reviewing applications from schools, students and vendors. According to GESA, nearly 15,300 families applied, yet thousands were determined ineligible.

It will take at least 15 months before Georgians will have metrics from GESA’s first review to evaluate whether the promise of the sweeping policy — better quality education and more competition for public schooling — is fulfilled.

Companies are leading beneficiaries

For now, however, data from the first dispersal of funds in July show dozens of private companies are the leading beneficiaries of the fledgling voucher system.

Amazon received the largest amount from the voucher funds, with $302,000 in sales. The next three largest recipients of funding were electronics vendors headquartered outside of Georgia.

The private school with the largest amount of funds from the voucher program was Newton County’s Covington Academy with $120,701. It is the only school to have received more than $100,000. Tuition there runs $5,500, plus fees.

In Coastal Georgia, the state authority ruled that some students from Liberty and Chatham Counties were eligible for the vouchers due to zoned public schools’ low rankings. Hinesville’s First Preparatory Christian Academy, where tuition ranges from $6,500 to $7,900, plus fees, has received the most money among private schools in the coastal counties from the program.

Vouchers failed for years

Georgia, unlike many other Republican-led states, has been slow to adopt school vouchers, one of the main educational policies championed by the Trump administration, although proponents of such vouchers have been pushing them for decades.

Back in the 1950s, the then, all-white Georgia General Assembly set up a vote on what its own supporters called “the segregation amendment,” which allowed the state to give educational money directly to residents instead of providing them with a school. That disappeared by the time of a 1983 rewrite of the state constitution.

In 2007, voucher supporters succeeded in passing a limited program called Georgia Special Needs Scholarship, which focuses on students needing special education. The state annually publishes data on that program, which is still active.

Conservatives have long sought to widen access to that program, but opponents from both parties have stood in their way.

In 2018, Republican Lt. Gov. Casey Cagle’s ambitions for governor were scuttled, in part over a policy that supporters say lets Georgians direct a portion of their tax dollars to private schools of their choice. On a secret recording that a political opponent made public, Cagle called it “bad public policy” but said he endorsed it to prevent the Walton Foundation from spending $3 million on behalf of his GOP rival, Hunter Hill.

“It ain’t about public policy,” Cagle said on the recording. “It’s about (expletive) politics. There’s a group that was getting ready to put $3 million behind Hunter Hill. Mr. Pro-Choice. I mean, Mr. Pro-Charters, Vouchers.”

In 2023, rural Republicans joined most Democrats in the state House of Representatives to defeat a first draft of the school voucher bill sponsored by state Sen. Greg Dolezal, a Republican whose suburban district north of Atlanta has only one school on the list of poorest performers. The first version of his bill would have covered all Georgia public school students.

Those Republicans who stood against the policy worried that vouchers would drain money from public schools in their rural counties, generally the only local educational option in their areas. Democrats, meanwhile, feared that vouchers would simply be a discount for wealthier families already inclined to send their kids to private school.

But by 2024, Gov. Brian Kemp put the weight of his office behind the issue and declared it time to support families in making the best choice for their children — whether that is public, private, homeschool, or a charter school.

Enough Republican holdouts signed on to help give the bill the minimum 91 votes necessary to pass the state House. Then-Democratic state Rep. Mesha Mainor of Atlanta also voted to support it, which later prompted her to switch political parties before her re-election bid. She lost.

How does the program work?

Eligibility for the voucher program depends on the elementary, middle or high school that students would attend, based on their address. If the performance of any one of those three schools is ranked in the bottom quarter of state performance, the student can apply for funds to transition to private education. But there is no statewide list of students with all three zones they inhabit, so there is no official estimate of how many students are eligible, either.

About one in four of the first students in the program come from families that earn more than four times the federal poverty income level. That number varies with family size but for a family of four, it means about $129,000. About 52% of the students are Black; most of the rest are white.

Public schools are ranked by the average of their last two overall scores on the annual College and Career Ready Performance Index — a measure of student progress and mastery of reading, math and science.

Schools’ CCRPI scores can swing up or down by more than 30 points a year on the hundred-point scale. The School of Humanities at Juliette Gordon Low in Savannah went from a 53.2 in 2023 to 69.7 in 2024. That gave it an average score of 61.45, low enough to land in the bottom quarter of schools.

Statewide, the biggest swing came at Atlanta’s M.A. Jones Elementary. Its 2023 CCRPI was 75.7; the next year it scored 40.9. Atlanta is considering consolidating the school with another.

A school can rise out of the bottom quarter quickly, but once a child is in Georgia Promise, they have priority to stay, regardless of any improvement in their public school. The state is set to update its school rankings by Dec. 1.

For eligibility verification, GESA requires families to submit paperwork showing their own address and the kids’ public school transcript or other official school materials. There’s an exception for rising kindergarteners who don’t have any records with a public school — about 32% off the first cohort.

Grading the schools

Public school performance is measured by hundreds of metrics published online.

The law requires private schools to give voucher recipients a standardized test — either a state one for the student’s grade level or some other national test GESA might approve. And private schools will also need to report on voucher students’ attendance, course completion and graduation rates.

GESA must make its first report to the legislature and the public on student performance, demographics and parent satisfaction in December 2026, once it has the benefit of a full school year’s worth of data.

But it is undecided yet whether that report will include school-by-school data. Some private schools will have so few students that detailed reporting could compromise student privacy. A GESA spokesperson said it would be premature to comment on the level of detail to be expected in next year’s report.

And the law does not specify whether poor rates can lead to the expulsion of a private school or vendor from the program. It gives GESA the power to take “corrective, remedial or preventative actions” to protect its interests, the public interest and student interests.

A state committee of parents with children in the system is set to adjudicate any family, school or vendor who feels wrongly excluded. However, that committee will not start work until after the close of the September student application period.

Asked how that committee would be chosen and whether its meetings would be public, the agency spokesperson responded, “It would be premature to comment on committee governance prior to their adopting rules and regulations.”

What’s next

Dolezal, the sponsor of the 2024 law, plans to ask his colleagues to amend the legislation when the Georgia General Assembly convenes again in January. One significant change he is seeking: a requirement that unaccredited private schools provide documentation from accreditation bodies confirming that the institution is making a good faith effort to complete the complex multiyear process.

Dolezal still hopes that school vouchers could be an option to all 1.7 million Georgia K-12 students.

That “is where I’m at ideologically and philosophically, and I would like to see Georgia get there,” Dolezal said in an interview earlier this month. “I don’t think we have — I don’t think we get there next year. So I wouldn’t be bringing a bill necessarily for that.”

![[Aggregator] Downloaded image for imported item #1146362](https://whitecounty.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/20250725SCCPSS-104-1024x683-1-696x464.jpg)